Christopher Ramsay: Could you describe why KJM’s depictions of African Americans are particularly powerful?

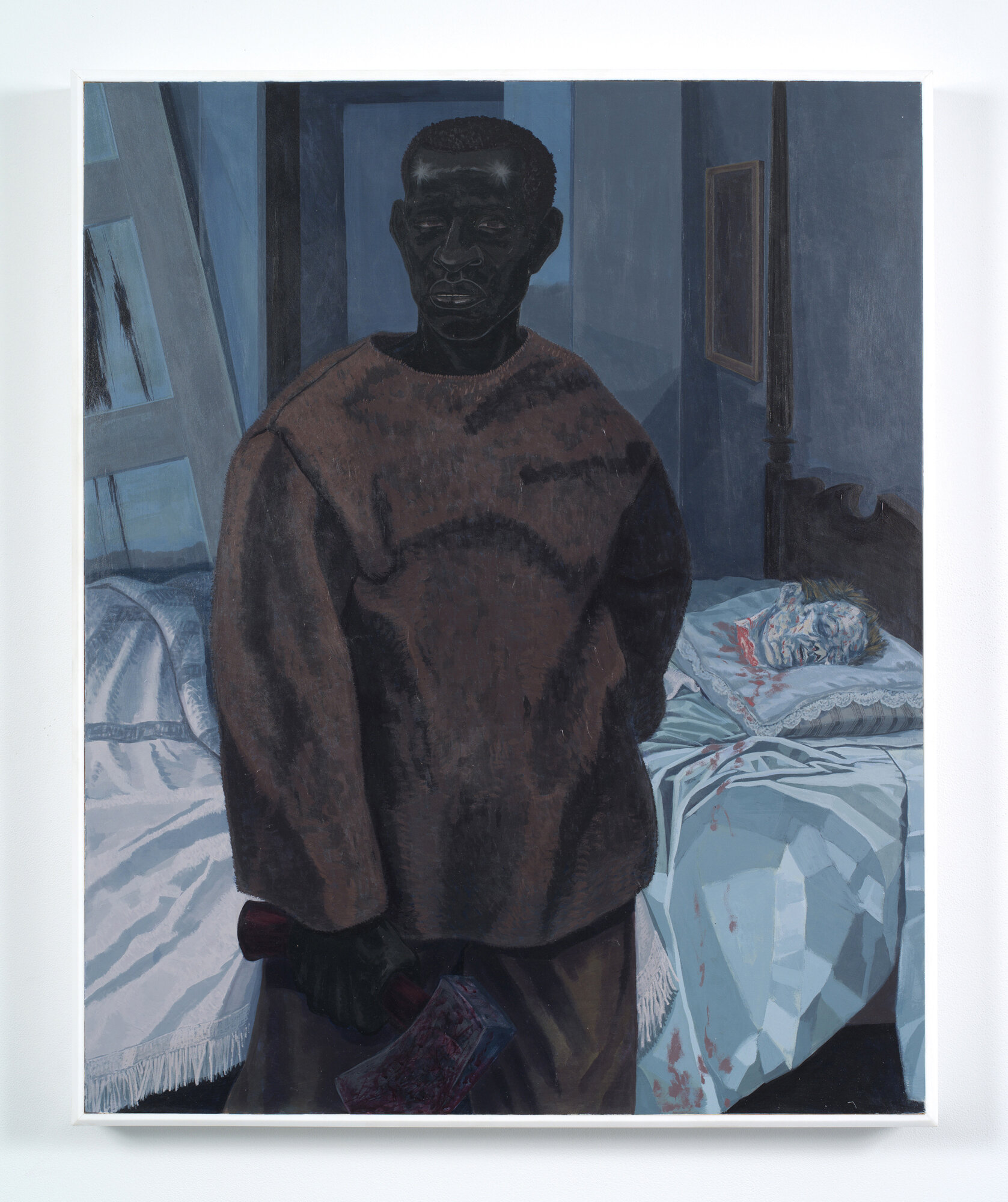

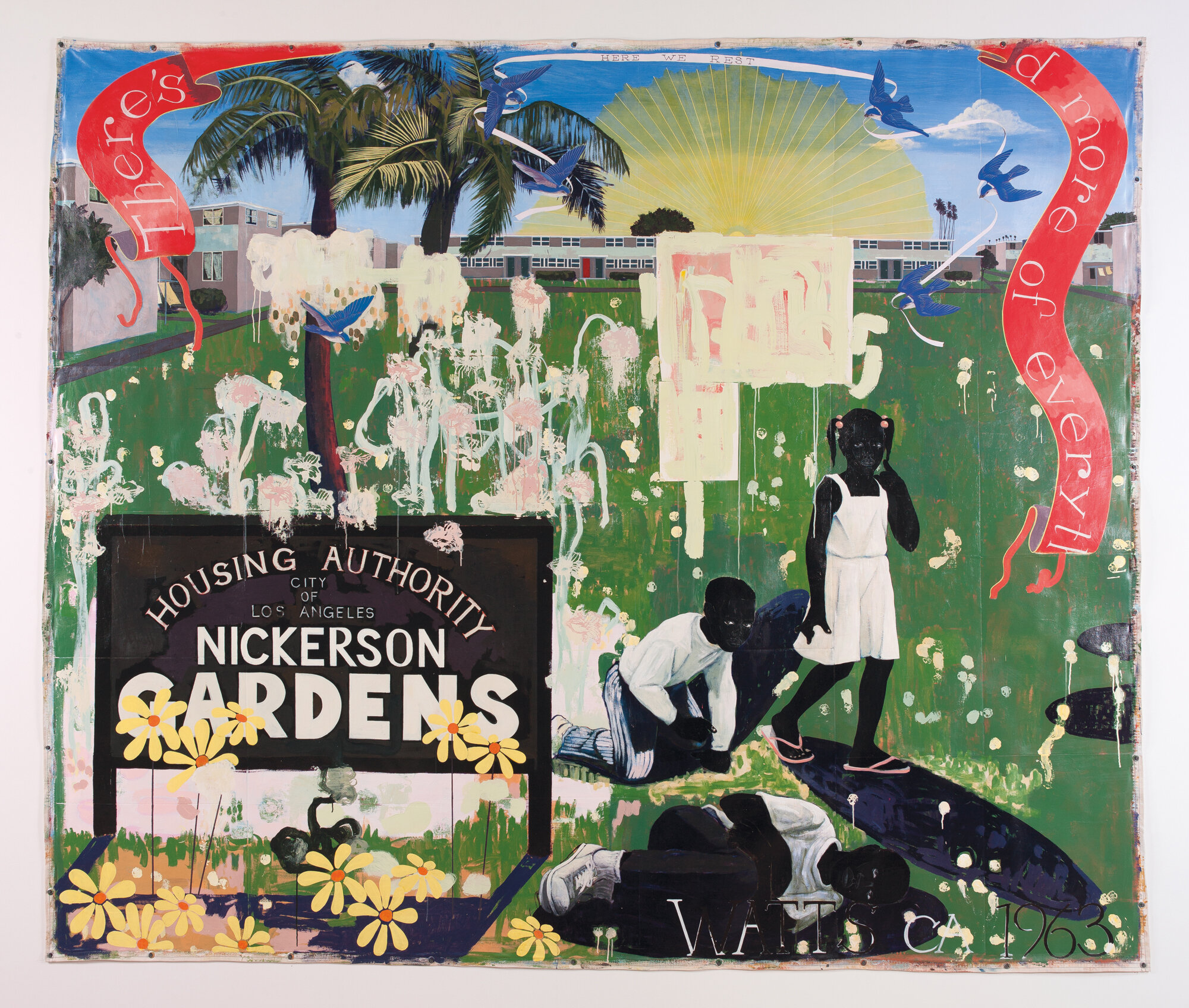

Helen Molesworth: I think the simplest answer is because he’s a great painter. Kerry operates consciously within the history of painting, so he carries within his head the now 600-year history of oil painting, and that means that every time he faces a blank canvas he faces a really daunting task. You’re in a crowded field where a lot of the ideas have already been not only invented but perfected, torn down, and reinvented. What’s different is Kerry has understood that when you went to a museum in the West, you were likely not to see images of black people.When you did see them, they were in the corner, as Magus, slave, maybe a weird sort of odalisque with a sexual charge, but they weren’t the protagonists of pictures in museums.And Kerry decided that wasn’t OK. So he very systematically set out a programme for himself over the last thirty years, to redress this enormous absence; so when all those paintings were brought together and everyone could see the fullness of the project, and everyone said ‘oh my god’, for thirty years he’s been ticking off the genres: history painting, check; portraiture, check; landscape painting, check; genre scenes, check; abstraction, check. People realised how white their experience of museums had been – how white their experience of art had been. It was this bracing, undeniable revelation. People were gobsmacked because the pictures are so epic – you’re combining the redressing of a historical absence with a high degree of excellence and you have something really combustible.

CR: In today’s sociopolitical climate, how do you think he considers his work and how it’s currently viewed?

HM: The show was on view in New York when Trump was elected and I know both from popular culture accounts and from personal accounts that a lot of people went to the Met to see the show as a kind of tonic. People were really quite devastated by the election and Kerry’s pictures on the one hand redressed this huge absence, and also pointed to the history and the legacy of racism, its brutality, its unethical-ness, its inhumanity. Those pictures create a field of hope. That complexity is really interesting, as when you’re in front of a KJM painting, one of the things you’re negotiating is your own internal responsibility for what you either know or don’t know about African-American history. You’re being offered a moment of engagement where you actually get to be your best self.That quality of Kerry’s work was very much in play when the show was on view.The timing was everything. Kerry and I talked about that a lot because we never thought the show would do what it did.We were making an art show, and that’s our job – he makes pictures, I make shows. But the way it landed amongst this extremely racist backlash to Barack Obama in the election of Trump, put it at the critical epicentre of culture. That’s really interesting – when art jumps out of its art world and into a much larger sphere of culture.We were lucky to have the show up when it was. Everyone knew it, everyone really wanted to believe that this country still had the capacity to be better. Kerry’s pictures offer you that.