CT: I think good work often comes out of obsession. Do you feel like still life is the current obsession?

JM: It really is. It’s so new for me, and I can’t quite get over it. It maintains my excitement. I’ll tell you something interesting. As a photographer, I made prints. I just sold a huge part of my archive. A year and a half ago, I sold 35,000 vintage prints out of the 55,000 I had in the studio.You can imagine with 55,000 prints around, I wasn’t interested in collecting objects. I’m not a collector of things. I collect moments of time and observations, and I make prints. But a few years ago, by some odd chance, I bought three objects for a friend. I tell this story in the book, in the first chapter, about my friend Johnny. I brought him these three objects, and I gave them to him because he’s a wonderful collector of things for other people. People send him out to hunt for things, and he’s just simply the best at it. Collectors come to this guy and say, “Can you find me a...?” and he will find them the something they’re looking for. But he doesn’t keep them for himself. He doesn’t have any real possessions. He gives everything away. I brought him these three dumb objects that I bought in France. As soon as we saw each other, he pulled out of his truck a huge piece of canvas that was used as a fireman’s net for people to jump out of burning buildings. For some reason, we threw the canvas over the fence with the hunk of it on the ground. I took the three objects from him, and I put them down on the canvas and we stood there together looking at them. I had this shiver run right through me and I thought, oh my god, look at that, these are tiny things against this gigantic background. I got my camera, and I made a couple of record pictures, just snapshots. For the next two days, I couldn’t stop thinking about them.What the hell does that mean? So, I borrowed the objects back from him, and I took the canvas and I made myself a still-life space. I just looked at these objects for a couple of weeks and I put some other things on it.They weren’t beautiful, they were dinged and rusty, dented and old.They had no measurable beauty. If I gave them to someone else, they wouldn’t say, “Oh my god that’s the most beautiful apple I’ve ever seen.” It just would have been this junk. However, a tiny Zen bell went ‘ding’ and that little bell was all I needed to know that I was on track. For me, it doesn’t have to be a big blow to the head, if I get a little tiny ‘ding’ it means that that ‘ding’ was more interesting than any other sound around me, and it’s the one that’s most difficult to hear, but I hear it. I always follow it.Through the decades of this book, you can see ten different turns in my life in which the Zen bell went off and I changed my course slightly, which meant that a new question about photography had arisen.A question that was interesting enough to take me off track and make me want to follow it wherever it’s going.That’s all there is to it. It seems to me that I am like Pavlov’s dog: when a little bell goes off, and I start to salivate, I go after that. Photography has shown me my life. It’s given me a life. I know it will give you a life too as long as you stay as intuitive as your description of what would it be like to love these people suggests. Or maybe it’s: what is there about them to love? That’s a very humanistic way of working, and I admire that because I think that’s at the heart of photography.

CT: Were you always working with the still life, but it’s taken until now to jump in?

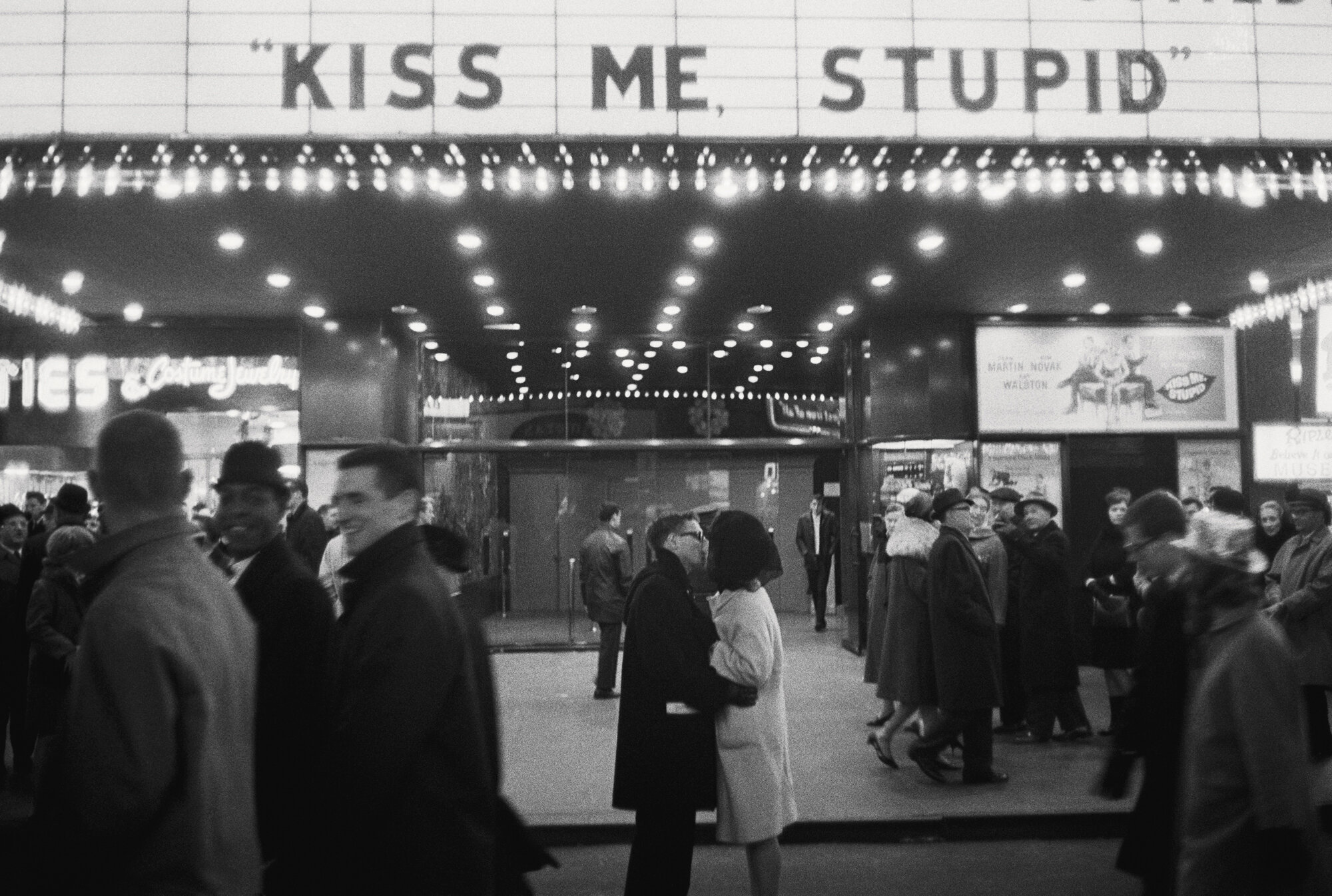

JM: I never made still lifes. I never arranged still lifes. Sometimes, and I’m sure this has happened to you, you get up from a dinner with four, five, six friends and the table at the end of the night is just strewn with dishes and wine glasses, and for a moment it looks beautiful in the candlelight because other people did it for me. It’s only an observation, but I never thought of it as a still life because I didn’t do it. Still life – no. I still carry a 35mm camera with me every day when I walk out of the house, and I did when I was using an 8x10 too. I tried to describe each of the phases in the book, what was going on for me in my life, as a photographer that prompted me to change subject or change the camera. Often it’s in need of greater description than the 35mm could manage.That came from John Szarkowski. I was very fortunate to see all of John’s exhibitions and to even be in a few of them. I got my education from John Szarkowski. One of the things that John once said, but also wrote about a lot in the Sixties and Seventies, was: “Look, you press the button, all the camera does is describe what’s in front of you.” He keeps on using the word ‘description’ in many of the essays he’s written. One day I was thinking about it, and I realised that colour describes more things than black and white, which is why I always used colour because it had more layers in it. It had more information in it. I’m making a certain kind of picture on the street now in which I have given up ‘the incident’. By which I mean the hook that we’ve used ever since Cartier-Bresson. Two people kissing on the street or people fighting – an incident. I was trying to diversify and get away from the single incident and spread a kind of non-hierarchical energy across the frame so that everything in the frame played in an interesting and fresh way in my mind. I wanted to try to see differently.As I stepped back and started to make these wider shield- like photographs without the incident as the central hook, I thought, ah I want to blow these up to 6 or 8 feet across.You just can’t with 35mm even with Kodachrome, as sharp as it was. It couldn’t go the distance. It looked great as a slide on the screen, after all, movies are made with 35mm, so the image on the movie theatre screen looked great, but of course you couldn’t see that it was moving all the time. I wanted movie-scale images, and I thought the only way I was going to do this was if I switched to a large-format camera. I actually wanted a 11x14 camera. I thought if I’m going to go big, I’m going to go really big, but Kodak didn’t make film for it.They said they would make it for me, but I had to buy $20,000 worth of film at a time. In other words, I had to buy the whole production, and I just didn’t have $20,000 hanging around doing nothing, so I bought an 8x10 camera, and that was fine. You could blow things up really big, and I started making 40-inch prints, before Gursky or any of those guys, who by the way studied my work and Stephen Shore’s work and William Eggleston’s work because Bernd and Hilla Becher told him he had to study the Americans. I was just inValencia a couple of days ago for an exhibition of a show and I bumped into Elger Esser, a German photographer from the Düsseldorf school. He was there with Gursky and Struth and those guys studying with the Bechers. He told me that story again how Bernd said to him: “You must look at the Americans; the Americans and their colour photography are the future.”

In a way, they came at a time when big printing was in a new evolution. It wasn’t like that in the Seventies.The biggest you could make was an 80-inch print, that’s how wide the paper was. So, I made 40–60-inch prints as regularly as possible. There also wasn’t a market. People didn’t really trust colour.They didn’t think it was stable, because it wasn’t. It really wasn’t. The show I just had in Berlin was all vintage prints from the guy who bought the 35,000 prints and they looked fantastic. Mostly because I printed them myself in my own darkroom and I had better chemicals than Kodak.